17 Jun 2019

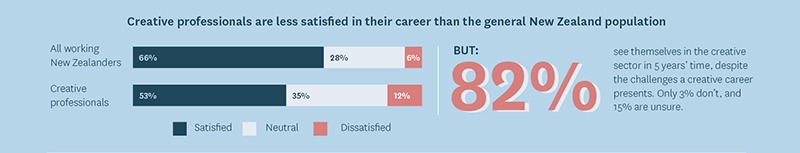

The recent survey of creative professionals we commissioned with our NZ On Air colleagues, through Colmar Brunton, has done what research is intended to do – shine a light on an area that was hard to see in detail and reveal some hard facts.

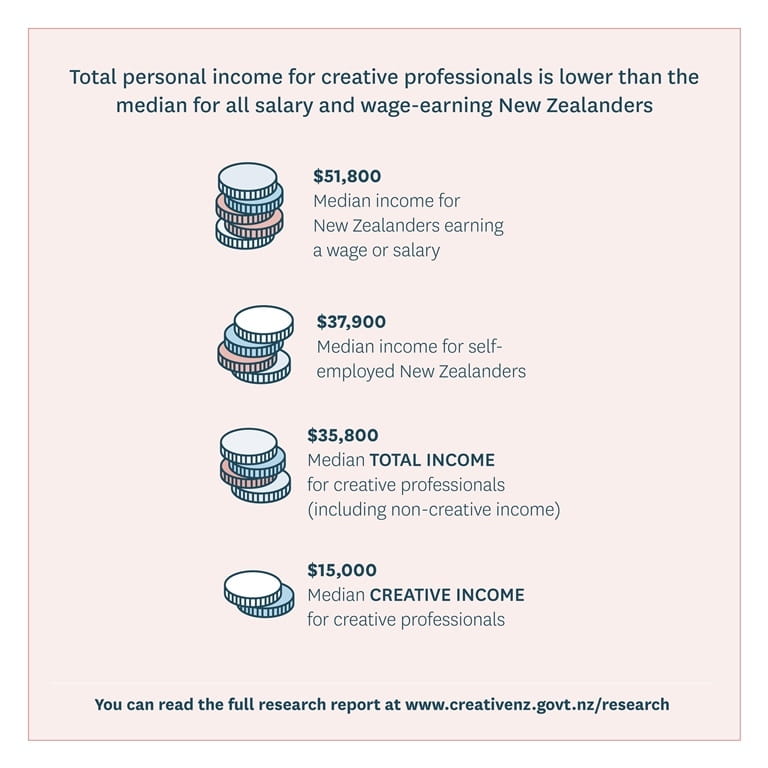

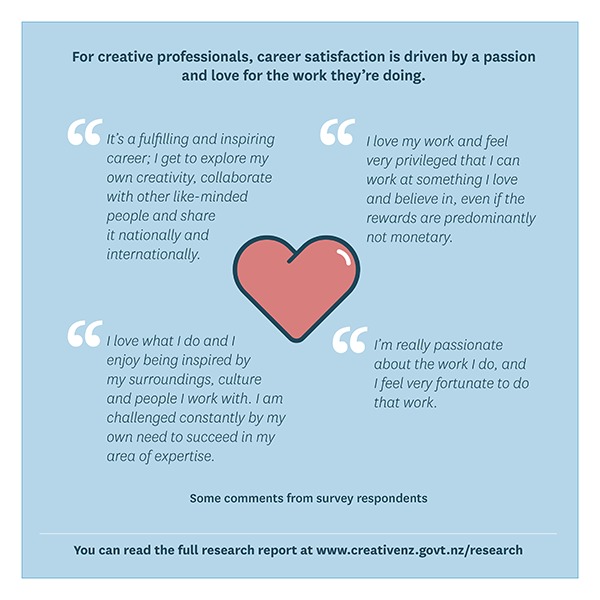

Those hard facts reflect a struggling sector and surely do not reflect the apex of our aspirations – Government, Crown agencies (like Creative New Zealand), employers and creatives alike.

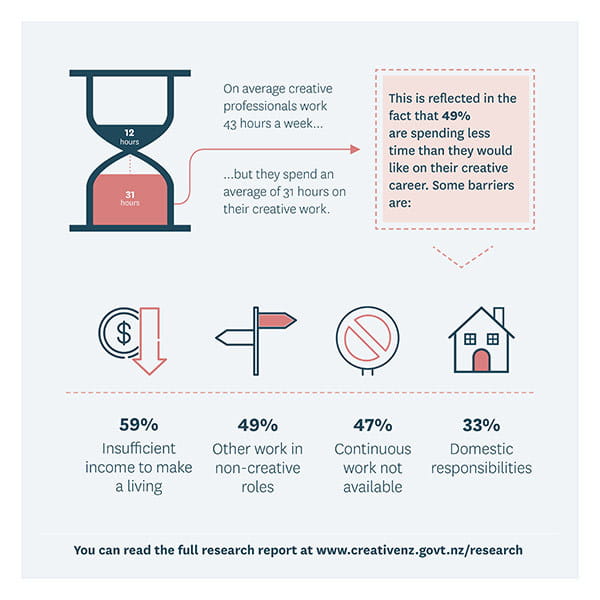

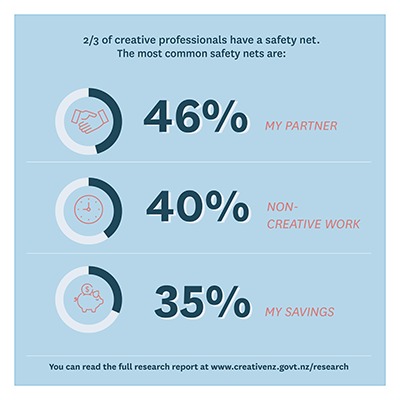

What the research doesn’t tell us is how we might change some of the uncomfortable realities it reveals, around remuneration, work opportunities and the structure of creative professionals’ work (which for most contemporary creatives is now the portfolio career or gig economy, aka juggling jobs).

Of course, if the issue of career sustainability was easy to answer, it would have been sorted already. We welcome the Government’s interest in this area, and its useful first step of additional investment announced in the budget.

Of course, if the issue of career sustainability was easy to answer, it would have been sorted already. We welcome the Government’s interest in this area, and its useful first step of additional investment announced in the budget.

Here at Creative New Zealand we will take some fresh action to support practitioners – in terms of fairer remuneration and programmes that support sustainability. We will also shortly engage with creative practitioners via a discussion document to get more insights and suggestions on priorities for improvement.

In time, we expect our efforts will be joined by the levers of Government and by the arts sector, who do much of the employment of creative practitioners.

More broadly, I see the research results in the context of the following three points, intentionally framed as questions. Together, these questions point to the importance of setting a wider agenda for a three-pronged approach – Government, agency and sector – in the work of advancing creative career sustainability.

1. Creative Professionals are already modelling the future of work - how can we tilt to that future?

The Creative Professionals research reminds us that most creatives are already leading the aforementioned ‘portfolio careers’, although perhaps not intentionally. A key reason for this is that the structure of many aspects of the creative industries is event-based or project-based, so compel this ‘gig economy’ approach.

Recognising the saliency of this way of working, improving its sustainability would be a good start and needs to be coupled with arming creatives with the technical and professional skills needed to manage a career as a fairly paid contract worker. As urbanist Richard Florida has said, explicitly supporting creative entrepreneurialism and the creative class is a net win for society, bringing tolerance and curiosity, and improving quality of life.

It’s not just the portfolio structure that lends itself to that ‘future of work’ model; it’s also the nature of the work. It’s increasingly recognised that, in a world that will soon have driverless trucks, machine learning and increased automation, the things that are human will be key to successful economies, communities and people. Creativity is the human spark that can ignite progress across the board.

This has been recognised by the World Economic Forum, elevating ‘creativity’ to 3rd place in its list of the most important skills workers will need by 2020 (behind critical thinking and complex problem-solving skills, and up from 10th place in 2015).

2. How can we reframe the way we see the contribution of creatives, using a 'wellbeing investment' lens?

The orthodoxy of pigeonholing artists solely into making an ‘arts and cultural’ contribution is unfortunate as it narrows the actual contribution artists make to society. A reframing is happening in spots but has a long way to go. For example, the contribution of creatives and creative thinkers to society traverses all four of the recently re-established local authority well-beings: economic, social, environmental and, of course, cultural.

There are many examples of ‘creatives’ delivering to well-being outcomes that are absolutely socially topical and important. A recent SPINOFF article focused on the play YES YES YES, created by Eleanor Bishop and supported by Creative New Zealand, which teaches teens about ‘consent’ and is a good example of the creative sector delivering in the education realm. The point is, if we’re to really embrace wellbeing we should open our doors, minds and wallets to what creatives could do to help.

I have a good friend who is a General Practitioner. Lonely, older folk who come mostly for a chat are a big part of his day. Drugs are not really the answer for them, rather company and purpose. Little wonder then that ‘Arts on Prescription’ has worked well in the UK from a client and financial perspective. Results in one area, after six months of a patient working with an artist, included significant reduction in demand for GP visits and the need for hospital admissions, and an estimated social return on investment of at least £4 for every £1 invested in arts on prescription.

3. How can we develop a more systemic approach to supporting creative practitioners and their sustainability

The ‘systemic approach’ here is a chronological path for many – pre-school, primary school, secondary school, tertiary, workforce.

There is a tautology here – teachers and whānau are more likely to support creative young people if they believe there is the prospect of a successful professional career. Many don’t (and you can see why) and steer people away from their creative passions – although the Creative Professionals research reflected more support today for our emerging creatives, from friends and family in particular, than older creatives experienced, perhaps reflecting a change in perceptions of creative careers.

At  tertiary level, it makes perfect sense that some people will want to study the arts for a rounded education. For those who want to earn a living as a creative professional, on entering the workforce they soon come to see that the creative and arts sector is not organised like other professions – and arguably suffers from the absence of a system view and voice common to other professions.

tertiary level, it makes perfect sense that some people will want to study the arts for a rounded education. For those who want to earn a living as a creative professional, on entering the workforce they soon come to see that the creative and arts sector is not organised like other professions – and arguably suffers from the absence of a system view and voice common to other professions.

For example, established doctors, accountants and lawyers have a deep role in training those who aspire to join their profession so they are ‘industry’ and ‘work’ ready once they have finished their professional qualifications. Consequently, there is generally a reasonable match between graduates and placements. After all, it only seems fair that, when you choose and pursue a profession, you can work as a professional.

Moreover, there is a recognised professional voice that can be presented to the world, to uplift the reputation of members and to regulate or engage with those who want to regulate it.

In essence, we know what the stanchions are that support other professions to be sustainable. If we’re serious about improving the career sustainability of creative practitioners, we should be interested in the same for them.

A model for the future, now

We’re living in a time when the future of work isn’t clear, yet in some ways the arts sector is ahead of the game, with increasingly sought after skills and flexible working practice the norm. We need to work together to fill the gaps that will help our creative professionals embrace their entrepreneurial bent and give them the skills and support to expect and receive fairer reward and a sustainable creative career. A strong arts sector will benefit us all.

Related items:

Budget 2019 funding recognises creative community

Creative New Zealand welcomes Government’s new investment in career sustainability for artists

Research reflects significant challenges of making a living as a creative professional in Aotearoa

Arts have an essential role to play in supporting better health and well-being outcomes

CATEGORIES: Advocacy Latest news and blog