01 Aug 2021

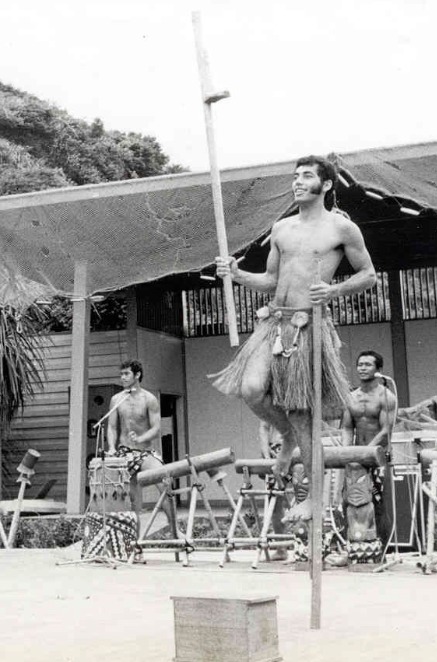

In recognition of Cook Islands Language Week, we spoke to Professor Jon Tikivanotau Michael Jonassen, a Cook Islands master heritage artist, about his life long commitment to culture.

The much-revered Professor holds degrees in government history, business and Pacific studies, but also a PhD in political science from the University of Hawai’i. While most of Dr Jon's career has been in service to diplomacy roles around the region, he is also a well-known composer of traditional Cook Island songs and has captured these in a number of books.

The Professor Emeritus, who has an MBE for services to Pacific region and Cook Islands, has ancestral roots to Avaiki Manavanui (Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Avarau, Tongareva, Manihiki, Mauke, Mangaia), Aotearoa, Norway, England, Germany, USA, Samoa and Tahiti. He also holds a traditional title of Tikivanotaua Mata‘iapo Tutara, under Vaeruarangi Ariki.

How did you start writing books on Cook Islands culture?

I started writing Cook Islands Māori songs when I was in grade six in Primary School. Not long after, I ventured into poetry developing a special interest in the multiple meanings of Māori terms and the power of idioms. Learning the various Māori dialects was also fun: “Get the paka soap in the fale kaukau,” was my early shower instruction as a child. My father and mother who were both school teachers instilled in me an appreciation for the importance of language acquisition. I was also always personally encouraged by many other writers to write my own people’s stories. They included Taira Rere, Roger Duff, Jim Siers, Ronald Syme, Ron Crocombe, Marjorie Crocombe, and others.

Listening to school teachers sharing stories about Snow White and Little Red Riding Hood in Cook Islands schools, reaffirmed a strong desire to write our own traditional stories of heroes and monsters. I began taking more special note of the indigenous stories that my parents and Vaiokura community Mamas were sharing with us in our home. And when I was punished (several times) for speaking Māori in Tereora College, I was rudely awakened into the real-power-play dictatorial world of politics. Since I usually topped my English class at school, I had particular difficulty understanding any logical reason, to punish me for speaking Māori? I made a personal commitment then, that no-one was going to force me to unlearn beautiful cultural images that I had learned as a child. I would always pursue learning my Māori language. I conjured up a thought then that perhaps one day, the prefect who kept placing me on detention would some day be buying Māori reading language books from me. I also treasured more the freedom to learn any language that I wished especially the languages of my various ancestors.

When attending a particular Pacific based information lecture at Brigham Young University - Hawai‘i I found the repetitious lessons distracting and was quickly becoming bored by the lesson. It was material that I was already very familiar with from schools in Cook Islands and New Zealand. Realising that it was just the beginning of a long four-month semester, I decided to take charge of my remaining semester experience. So I always sat in the front row, asked a couple of questions, at the beginning of each class, and then spent the rest of each class period writing Cook Islands stories that I had heard from my parents. I drew sample pictures to go with the stories because I did not want Fiji looking illustrations, and then sent the manuscript to Professor Ron Crocombe in Fiji. He submitted the material to USP and it was my first published book entitled, “Cook Islands Legends.” But to my horror, my pictures were included without any changes. Professor Ron tried to reassure me by declaring that my pictures were “free flowing with no rules being followed.” We became great friends but I still never understood what he meant. At his prompting, I wrote many more chapters for a variety of Cook Islands based themes and stories. But I never submitted any more illustrations to him.

Incidentally, some eleven years later in 1993, I returned to Brigham Young University - Hawai‘i as a Professor and my previous Professor was still teaching there. I told him about my first book and apologised, how I had approached his class. He was amazingly understanding and complimented me for using my time wisely. He added that he was happy that I did not disrupt the lessons and more importantly, did not drop out of the class.

“In the Pacific, we use baskets not boxes. Our ancestors knew that some things are meant to escape from the basket.”

As a Professor now working in a United States competitive system I quickly learned about a common popular slogan: “Professors must publish or perish.” I realised that to progress up through a teaching career pathway from Assistant-to-Associate-to-Professor, I needed to specialise in an area of research, to ensure original publications. In that 1993 year, I looked at the potential focus options being either Hawai’i, Aotearoa, Japan, or Cook Islands. Hawai’i was the most tempting at that time because of its close language and cultural proximity to Rarotongan and because I was working there. But I thought, “If I, a Cook Islander does not study the Cook Islands under such circumstances, then who will?” I subsequently chose Cook Islands and thereafter conducted much of my research and writing efforts on a variety of issues, and stories linked to Māori indigenous people linkages in the Pacific, particularly Cook Islands Māori. For twenty years from 1993 to 2013, I researched, wrote articles, chapters, and books, create workshops and made conference presentations. Even produced several audio and video productions and pursued multiple research leads while remembering much of what I learned from my parents, and the Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Atiu, Tongareva, Palmerston, and Mangaia communities that I grew up in. I also re-read much of my notes from the times that I had headed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Culture. The hard work ethic learned from my childhood helped me a lot.

What was the most compelling thing you discovered on your writing journey?

There are many amazing indigenous valuable knowledge from our ancestors that is too often marginalised or ignored. Some of the carriers of that knowledge are often unaware of the precious nature of the information that they have been gifted with. Others have the captured information and are prepared to share but need encouragement and assistance. Much of that information will sadly slip into oblivion unless more support is urgently made available to reveal, collate, analyse, or simply just to publish what still remains. Religious fanatics, racist unapologetic antagonists, and unqualified political appointments in key positions in government discourage and even undermine potential progress. And routine unsupported verbal niceties from politicians about keeping Māori and culture alive only serve to dampen the conversations and marginalise the ancestor’s stories. Rare windows that project ancestral voices and images is sadly now captured or being understood by only a few who could far too quickly become buried by the general lack of meaningful support.

There were times since the turn of the new millennium that I felt that perhaps I had chosen the wrong focus. Maybe a focus on Hawai’i, New Zealand, or even Japan might have attracted more support. Because the reality is that until recently, I have witnessed negligible support assistance from the Cook Islands government or any show of support from private sector institutions with any genuine interest in supporting Cook Islands publications. Almost all of my publications in the past forty years were achieved through academic supporting individuals and educational institutions such as University of South Pacific (Fiji), University of Hawai’i (USA), Brigham Young University (USA), Bergen University (Norway), University of Guam, or even the Taiwan indigenous peoples foundation. Even the much-appreciated funding that sometimes rolled over from AUSAID or NZAID was often squandered. I look at the many manuscripts still on my computer and tend to believe that writing in Māori will remain a kind of leadership that will always conjure up the four “S’s”of Surfing: (1) Catch a good SURF, (2) Watch out for other SURFERS, (3), Watch out for SHARKS. (4) Watch out for S**t. The challenge begins with finding the good surf. But the other “S’s” remain problematic.

What motivates you to continue the work you do?

I love the people and the islands of the Pacific in general. I have studied the Pacific, lived in many parts of the Pacific (Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Tahiti, Suva, Noumea, Chiba-ken, Nauru, Hawai’i, Aotearoa, Bali, etc), served the Pacific region in various capacities (in the SPC, PIDP, SPREP, SPEC, and SPF), written much about the Pacific, and hosted many people from the Pacific in my home. I was adopted by a tribe in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, learned various Martial Arts of Japan, and danced the various styles of islands across Te Moana Nui A Kiva. I love the cultures and the languages, especially the Māori language in particular. Where else would you go in the world to find, that on one island the word for fight is “ta” (Rarotonga island), and the next island it is “te” (Mangaia island), and then on the very next island it is “to.” (Aitutaki island). Or better still, in Rarotonga you say “au” to mean “me” but 110 miles in Mangaia island next door, “au” means “you. Understanding people is at the core of what I do, and I believe that it is genealogy (people) that connects or disconnects us. Not the ocean as many have been arguing over for some time now. We do not put things in boxes as the researchers try to do when they focus on a research topic. In the Pacific, we use baskets not boxes. Our ancestors knew that some things are meant to escape from the basket. I have super recharged my motivation because of the very positive and real encouragement coming from Creative New Zealand, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of New Zealand, and the Ministry of Culture of New Zealand.

I do appreciate the small but highly impactive assistance coming from the current Secretary of the Ministry of Cultural Development Mr. Antony Turua, and the Prime Minister Mark Brown, who have been very supportive of my efforts to publish. The emergence of Mana Heritage Publishing Limited initiated by my son Tamatoa Jonassen has also been a particularly great vehicle for channeling Māori informational books. The result is that even with minimal support, we managed to launch 12 books in recent eight months covering legends, ghost stories, drumming, songs, language acquisition and traditional verses of wisdom. The life saving water bottle did finally arrive while I am still alive, but it is still in inadequate amounts compared to what really needs to be done. We have still barely scratched the surface. And I am acutely aware that most of our Māori people have migrated to Aotearoa and they are wanting help with their Māori language. My surfing commitments needs to catch a great wave heading out in that direction.

As long as I am breathing and can write a logical sentence, I am ready to publish what is still flashing on my computer and retained in my mind. The old men Papa Tangaroa Kainuku, Papa Tere Ngapare, Papa Karati, and others who shared their sacred information with us, while pointing to me to ensure that it must emerge in print one day, still flashes reminders in my mind. Traditional knowledge on a myriad of topics can still be retrieved, if we hurry. So I continue to watch out for other surfers but am still waiting for the good surf.

What is your favourite Cook Island proverb that you’d like to share?

I have two Kama‘atu (Verses of Wisdom) that I always use:

Taka‘i koe i te papa enua, akamou ki te pito enua. A‘u ite marae kia tapu, i tere ei to‘ou rangi. A-Io-kokou.

Whenever you go to any new place, connect yourself and remember God. And move forward. Do not keep looking backward.

Mou ite ko, mou ite ‘ere. Kia pukuru o Nga vaevae, kia Mokora o kaki.

Hold on to the spear (with your right hand) and hold on to love (shake with your left hand). Anchor your legs like a breadfruit tree and keep your neck flexible like that of a duck. In other words, be prepared to be friends and be ready to defend yourself. Hold on to your principles but be willing to listen to the views of other people.

What is an important part of your artform you’d like people to know about?

Language and identity is my focus and my story telling comes in a variety of mediums. To me, Māori is a language of love and it is at the core of all my work. Be it song (vaiata), prayer (karakia), poem (purua), chant (pe’e), melodious chant (amu), drum sequence (rutu), carving (tarai/akatikitiki), dance (ura/koni/hupahupa/ori/kosaki), song ending (pe’e akareinga), verse of wisdom (kama ‘atu), or an acrylic painting (tu-tu- parai). I work in all these mediums and words of love projects the power and imagery that I want to capture and portray in order to tell an important story as well as possible without compromising the indigenous element of the message. My language is the mirror of my culture. My words project my identity. The “Who I am, begins with my Ha and ends with my own Io-kokou.”

How will you be celebrating Cook Island language week?

I will develop a second part to a special song that I wrote some years ago entitled “Te Roimata,” that reflects a broken-hearted father, who still wonders why her beautiful young daughter sadly took her own life. The song wishfully cries, “Naringa uake te roimata e kauvai ki te rangi, ka tiki atu au iakoe na runga i taku vaka. Kia kite uake i to mata.” If only tears were a river to heaven, I would sail on my canoe to see you again.